I just ate 10 steaks in one hour!

Recently, I was asked to evaluate 10 different cuts of steak from two different beef suppliers for an upcoming restaurant opening. All of the beef was Certified Angus or Prime and all the steaks were prepared the same way (salt and pepper over a flame grill) by chef Tommy Chavez. I paired each steak with three of my wines, 2014 Cab Franc, 2014 Superstrada (Sangiovese/Cab Sav) and 2015 RWSC (Bordeaux Blend).

What did I learn?

First, that I consumed about 3 pounds of beef! More importantly, not all steaks are created equally and no two steaks paired equally well with the same wine. All the steaks were delicious, as it’s difficult to go wrong with prime steaks expertly cooked, but there were differences in texture, density, ‘meaty’ flavor, chew, tenderness, and fat content.

The most dramatic difference in flavor, texture and wine pairing was a prime bone-in New York strip (Club steak) versus the prime boneless NY strip.

My 2014 Cabernet Franc and 2014 Superstrada paired nicely with the boneless NY strip. Complimentary flavors, the steak was lean and well textured, my wines integrated well with this classic restaurant cut.

Change gears to a longer cooked bone-in NY strip a.k.a. Club steak and suddenly the integration of the wine with the steak changed. The bone itself was flat and nearly 2 inches wide and covered the length of the strip, which effected cooking time. Whatever the bone and cooking time did to change the flavor profile of the steak was dramatic enough to favor a more tannic and heavy-weight wine. The Cab Franc didn’t have enough heft or tannin to hold up to the Club steak. Superstrada was good, but showed better with other steaks.

Enter the 2015 RWSC.

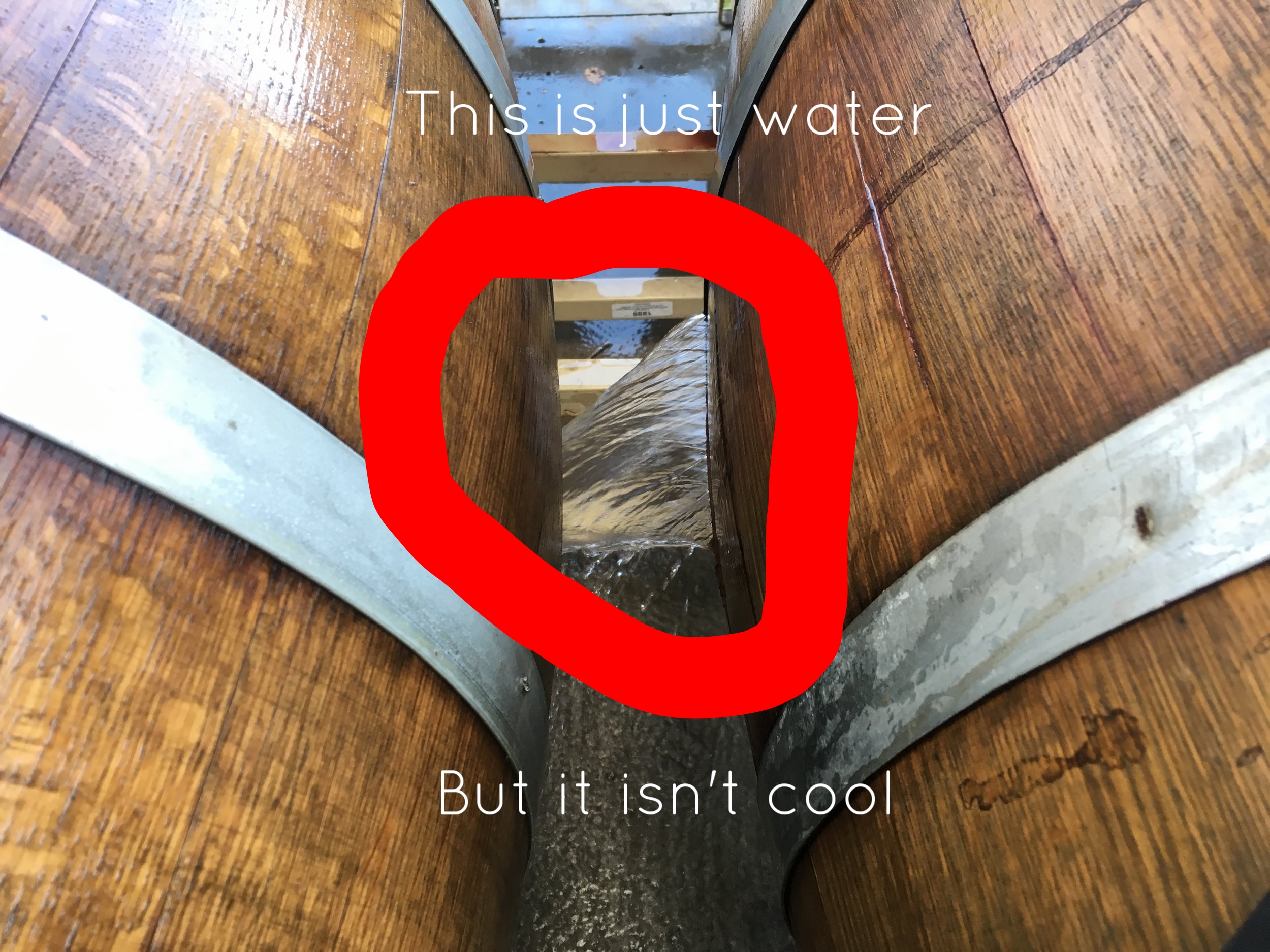

The 2015 RWSC is my 50% Cabernet Sauvignon, 25% Merlot and 25% Cabernet Franc from Dry Creek and Alexander Valley, with a 50% new Minnesota 36 month medium toast water bent oak and 50% neutral oak profile. Yes, I’m being very specific about my oak. Simply calling it “American oak” is an inadequate generalization.

While the 15 RWSC paired well with nearly every steak in the line-up (except perhaps the filet mignon where the wine overwhelmed the lean cut), it shined with the Club steak. This is where some combination of alchemy, meat sweats, and badly needing a plate of fries might be affecting my palate, but it was an enlightening moment in the tasting. How could one wine and one steak pair so well together? Why is this pairing so outstanding? This isn’t just me bragging about my wine. I’m sure other wines would have paired wonderfully, but in that moment, with those selections, the RWSC shined bright.

Next time I’m asked to evaluate steaks, I’m bringing more wine.